How Banks Prey on the Poor

When I was about eight years old, I opened my first bank account. It was a passbook savings account, and I’ll never forget the smiles on the bank managers’ faces as they patiently helped me fill in all the necessary paperwork. At the time, I assumed the smiles were inspired by the cute novelty of a little boy opening his first account, but upon reflection, I realize they were smiling at me the way Dracula smiles at his next victim.

“Come hither,” they beckoned helpfully. “I think you’ve got something on your neck.”

That experience 30 years ago was my last pleasant banking transaction. Since then, my banking career has been a nightmare of hidden fees, overdraft charges, denied loan applications and collection agents. Banks refer to their victims as customers, but a customer is someone whose repeat business one is trying to earn. Banks act as if they are doing you a favor by allowing you to open an account.

I have a friend who refuses to open a bank account. He keeps his money in a cookie jar on the top shelf of his cupboard. When he gets the desire to buy something like a new computer or a stereo, he simply saves his cash in the cookie jar until there’s enough to make the purchase in question. He pays his rent in cash; he buys money orders for his utility bills and all other expenses for which cash is inappropriate.

I used to make fun of him for his lowbrow approach to finance. Many times I derisively told him of the old Lithuanians I saw while waiting in line at my bank in Chicago who would come in every Saturday to count their money. The bank tellers wore expressions of frustrated resignation as the distrustful oldsters would demand to see their money and count it. I laughed cruelly at the way the old guys never realized that it was the same $5 thousand being counted over and over.

But who’s laughing now? As I write this, my checking account is overdrawn by $149.00. Every day it’s in the red, they add another $5.00. Are they doing this to earn my repeat business?

Those old Lithuanians are right to distrust banks. And so is my friend. Here’s why:

There are several methods banks use to extract as much money from their customers as possible. I should say from their poor customers, because the true purpose of almost every bank is to serve the rich at the expense of the poor. According to the New York Times, banks received over $30 billion in overdraft fees in 2001. Rather than offering overdraft protection to the working poor at a reasonable interest rate of, say, 10 to 20 percent, depending on the customer’s credit worthiness and length of employment, banks instead agree to cover bounced checks and debit card transactions and charge a fee of $20.00 to $35.00 for each overdraft. That means the $2.00 cup of coffee you purchase using your debit card two days before payday could end up costing you $37.00 or more. In effect, the bank is offering you a loan at an interest rate of around 190 percent. If you tack on the $5.00 or more per day many banks charge overdrawn accounts, the percentage rate climbs to

over one thousand percent. That had better be one damn good cup of coffee.

But that’s not all. Most banks use many shady tricks to maximize the possibility of your being overdrawn. Here’s one little trick banks use to exploit their working class clientele:

Let’s say you have written several checks this week. The first check was for $650 for your rent or mortgage payment. The second check was for $45 for your phone bill. The next two checks were for around $20 apiece for gas and electric service. Then another one for around $40 or $50 for groceries. Then, throughout the week, you wrote three or four more checks for between $5 and $10 apiece for lunch. On top of that, you stopped for coffee a couple times on your way to work and wrote checks for around $2 each time. Throw in a pack of smokes or a six-pack of beer here and there and by payday, you’ve overdrawn your account by $15 or $20. Well, rather than debiting all the small checks first and then charging the $35 overdraft fee for the $650 rent payment, they debit the largest checks first so that they can charge the $35 overdraft fee several times over on all the little checks. Don’t believe me? Check your bank statement at the end of the month.

What’s more, most banks increase the overdraft charge if you’ve had more than a certain number of overdrafts in a given period of time. If you’re like me, the first pay period of the month can be difficult because rent and most utility bills are due by the 5th of the month. The obvious solution is to apply for overdraft protection. Overdraft protection provides the customer with a line of credit that kicks in automatically when expenditures exceed the amount of money in the customer’s account. The loan is paid back usually at an interest rate similar to that of most credit cards.

Unfortunately, the bank customers who need this service the worst – ones who find themselves in the red about once per month – are the ones least likely to be approved for such protection because they are considered bad credit risks. Paradoxically, one of the things the bank looks at in considering customers for overdraft protection is how many overdrafts the customer has had within the last 18 months or so. When my application for overdraft protection was denied for this very reason, I decided to create my own overdraft protection. My current financial tormenter, U.S. Bank, offers a service called a “goal savings account.” This service automatically transfers a certain amount of money – in my case, $25 – from my checking account into my savings account once per month. Since they would not approve me for overdraft protection, I asked them if they would set up my accounts such that if I overdrew my checking account, the needed sum would be transferred automatically from my “goal savings account.” They gladly agreed. What they failed to mention, however, is that each time such a transfer occurs, my account is charged $5. So, if I have $2 in my checking account and I write a check for $5, it will cost me $5 to transfer $3 from my “goal savings account” to my checking account. Their failure to notify me of the $5 charge resulted in both my accounts being overdrawn.

In effect, U.S. Bank – like all banks I’ve encountered – is like a shark, no wait, a vulture, pouncing on the animal in distress and regurgitating the digested flesh into the waiting mouths of the rich who sit uselessly squawking in the nest. Or something like that.

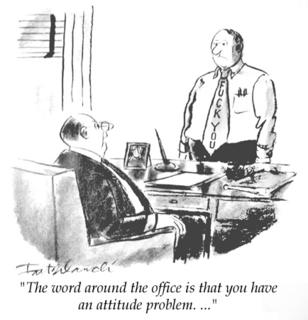

When you take all this into consideration, the word “customer” takes on tragicomic dimensions. What if a tailor treated his customers the way banks treat theirs? If he knew you were poor, he would sew the buttons onto your shirts in a way that guaranteed they would pop off the second or third washing and then charge you to replace them and increase the replacement charge by 10 percent every fifth button. He would simultaneously do exquisite work for his rich customers while giving them deep discounts and free alterations and repairs. Plus, he would be rude and dismissive every time you entered his shop. Come to think of it, this is precisely what tailors do, only they’re not tailors any more, they’re The Gap.

To add insult to injury, the advertising campaigns for most banks are patently dishonest. TCF Bank in Minnesota claims in their ads to offer “totally free checking,” while First Bank in Kansas tells its customers to “relax…you deserve consideration.” This advertising approach gives prospective customers the false impression that if, like roughly 3 million Americans, they are living paycheck to paycheck and find themselves in financial difficulty from time to time, they can count on the bank to help them out. This is a reasonable assumption. Why else, after all, would someone choose to keep his or her money in a bank?

There are three reasons that I can think of. First, banks are insured. If the bank is robbed or destroyed in a fire or tornado or some such calamity, the customers’ money remains safe and sound, whereas if my friend’s cookie jar is stolen or destroyed, he’s shit outta luck. Second, customers can earn interest on their deposit, albeit a tiny percentage. The third and most compelling reason someone might want to keep his or her money in a bank is Purchasing Power. If, like many Americans, you find yourself a little light towards the end of the pay period, you can simply “relax” because “you deserve consideration.” This relaxation, though, comes at a very high price. And the poorer you are, the higher the price.

Another scheme employed by many banks is a system of bizarre and constantly changing rules regarding when deposits and account transfers are posted. If, for instance, you make the deposit in person at a teller, it posts at one time, but if you make the deposit at an ATM, it posts at a different time. Many banks offer a 24-hour telephone line that customers can call to check their account balance, but this, too, is a ruse. On more than one occasion, I have called the number and made a purchase based on the balance information provided only to incur an overdraft charge because some previous purchase or debit was not yet reflected in the amount stated.

The American Heritage Dictionary defines customer simply as “one who buys goods or services,” but the American banking system has its own definition: “One who pays a lot for services, but receives only punishment.”

There is a tiny ray of hope, however, for the working poor who prefer not to keep their money in a cookie jar. It’s called the Credit Union.

Credit Unions are non-profit (if there is such a thing) banking institutions that, for the most part, act in the best interests of their customers. The idea behind credit unions is that, as with all unions, individuals obtain more power and autonomy when they work together.

The first credit unions were closely associated with labor unions. Teachers or plumbers or carpenters or journalists would pool their financial resources to provide low interest loans to the union’s neediest members, thereby providing assistance to working families who had been forsaken by traditional banks. The problem was that in order for credit unions to retain their non-profit, tax-exempt status, membership was required to be restricted to particular groups, such as trade unions or farmers or very small geographical areas such as townships or counties.

The Credit Union Membership Act of 1998 changed all that. This act allowed credit unions to significantly expand their eligibility without endangering their non-profit, tax exempt status. As a result, credit union membership has grown from about 64 million members in 1992 to almost 83 million members in 2002. And according to the Christian Science Monitor, Credit union-issued loans increased from a 16.1 percent share of the national market in 1992 to 17.1 percent in 2002.

Of course, traditional banks are pissed off about this development. And why shouldn’t they be? The $30 billion-per-year overdraft cash cow upon which they’ve been feeding is walking out the door.

“Once, members of a credit union knew each other and pooled their resources to provide credit for their co-workers and neighbors,” laments the American Banking Association web site. Today, the diatribe continues, credit unions can serve entire states. “Despite this departure from their original mission, these credit unions continue to be afforded special treatment, including exemption from federal taxation and from the regulatory responsibilities that apply to commercial banks.”

Well, boo hoo. Congress has acted on behalf of its constituents, for a change. Whatever will those poor, mistreated banks do now? I guess they’ll just have to take their $30 billion bat and ball and go home. When will these insouciant greed heads ever learn? Had they treated their working class customers with respect when they had the chance, they wouldn’t be witnessing this exodus into credit unions today.

But this doesn’t mean things are all peaches and cream for working class Americans. Credit unions still require a credit application to qualify for loans and overdraft protection, and with many such customers emerging bruised and battered from commercial banking’s rapaciousness, credit histories unfairly reflect poor ratings.

to be coninued

On Christmas Eve, NBC aired that timeless classic, “It’s a Wonderful Life,” starring Jimmy Stewart. As I watched it for the gazillionth time, I was struck by the irony of the event – especially during the Ameriquest Mortgage commercials.

On Christmas Eve, NBC aired that timeless classic, “It’s a Wonderful Life,” starring Jimmy Stewart. As I watched it for the gazillionth time, I was struck by the irony of the event – especially during the Ameriquest Mortgage commercials.